His book The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture has been translated into several languages, and when it comes to empathizing with plants, he is one of the greats. A conversation with philosopher Emanuele Coccia.

Emanuele, a professor for the history of philosophy at EHESS in Paris, writes about the beauty, the mind, and the soul of botany, showing that plants are the unrecognized rulers of the world.

FYTA: Your book is remarkable because it looks at plants from a philosophical perspective, instead of a scientific one. How did you come up with the idea?

Emanuele Coccia: When I was a teenager, my parents sent me to a school for agriculture. There I worked with plants every day for five years. It felt like being in exile, because agriculture wasn’t considered a part of “culture”. At the same time, it was an extremely interesting experience, because I had to try and understand life forms that can’t communicate in a way animals or humans do. This period had a lasting effect on me. But what really triggered the idea was a visit to the Fushimi Inari Shrine in Japan. It is like a forest in the middle of the city. For a person socialized by Western culture, it is a psychedelic experience. Strolling through the Shrine, I told myself I had to write something on plants, and somehow consolidate these two sides of my life. Because even though I was still reading about plants, biology and botany, I was giving classes in philosophy of religion and aesthetics. I wanted to merge both of these souls.

"If we say that plants are life forms, we also have to admit that we are cannibals"

In your book you’re talking about the physiocide, the fact that plants aren’t a topic worth exploring within the humanities and the sciences. It wasn’t always this way. How do you explain the phenomenon?

Hm. Some of the reasons go way back: Aristotle for instance, the father of Western thinking, wrote about everything but plants. This blindness exists since millennia. And on the other hand, this might be the case because we can’t help but eating plants every day, and it’s difficult for us to give them the same status than cats or dogs. Otherwise we would have to challenge our most basic ideas.

If we say that plants are life forms, we also have to admit that we are cannibals on a certain level. But of course: our life is always that life which others have developed first, and which we have stolen or internalized for ourselves.

On the other hand, we are not doing anything against that. I have a little daughter now and in the children’s books she reads, animals are depicted as characters, whereas plants don’t have a name and no identity, they are just “nature”. This is why it’s hard to overcome this blindness.

One of your core arguments is that in order to understand the world, we have to understand the plants. Because it’s the plants, as you write in your book, who “make world.” By saying this you’re turning anthropocentrism completely upside down and are describing plants as higher beings which possess skills far more advanced than ours. However, in other parts of the book you say that everything should be perceived as equal.

Yes, that is true. (laughs). It’s like this: we are so used to understanding Darwinism in a way which turns spirituality or thinking into a mere play of atoms and molecules, and which implies that everything can only be understood in a scientific sense. But the deepest meaning of Darwinism is actually the opposite. It suggests that everything that can be found in humans is going on in other life forms as well: the metamorphosis. On this level, I think, all life forms are equal; they think and feel equally and have intentions. Regarding the hierarchy, there are some who contribute more. Plants are life. Their contribution to the existence of the world is huge.

"We have to understand what plants are in order to understand what we are."

You consider plants to be mediators, which explain life to us. What would change if we were capable of understanding plants better?

Well, everything! Here we are in the woods for instance. It is one thing to think about the forest as a place in which all things are green, like the walls of an apartment. But it’s another to consider that this place is made up of living, sentient beings, which we don’t talk to, but have a relationship with.

Even the city would be a completely different place if plants wouldn’t be seen as ornaments, but as living beings, which take their space and have a right to feel comfortable.

Another important point is that we can’t help but eat plants. Which means that our relationship to our food and the actual act of eating would be very different, if we realized that we are consuming living beings. This act of eating could be described as a reincarnation in a literal sense: We consume the body of another living being. If we were aware of this, we’d show more respect for life.

There are many sensual passages in your book. Often you write about sex. Sex as a cosmic event, as a moment in which identity dissolves; flowers and blossoms as carnal. Some sentences sound like softporn for sapiosexuals. Which role does sexuality play in your plant philosophy?

A huge one–but not only as part of the philosophy of plants. Sexuality is essential for us, but the problem is that there is a misconception about what it is. Sex doesn’t only mean to be able to engage in a sexual relationship with someone. It also means that my body originates from the merging of two identities, my father’s and my mother’s, which have to result in a compromise. Sex therefore also stands for the fact that my procreation can never be the precise reproduction of my identity, but blends with the rest of the world. This is what sex stands for: the fact that we have to constantly merge with the world.

Does that also imply that in a way, we’re constantly having sex with plants?

Not only with plants, but with ideas, words … Sexuality means that we are changing constantly. When we eat, our bodies merge with other bodies. In order to remain my body, my body has to ingest the flesh of another body. Which is also part of sexuality I would say. So our bodies are built from this plant flesh in an implicit way. We are a metamorphosis. We have to understand what plants are in order to understand what the world is and what we are.

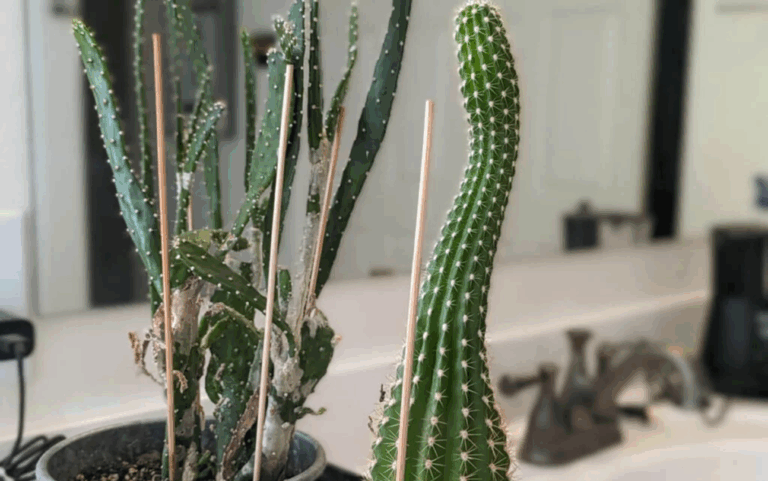

Do you have plants at home?

I just had to move and unfortunately leave my plants behind in the process. Usually yes, a lot of them! It is similar to having kids: It gives you a great deal of structure, because they make you do certain things for them every day. Being a father means understanding that your life depends on other living being’s lives. And this is something I realized by exploring plants: that we can only survive through relationships, and as part of a network.